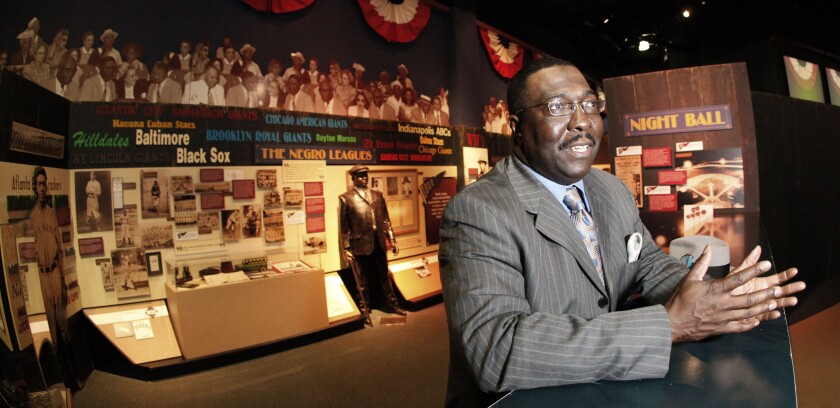

Every time Bob Kendrick steps out of his office, the President of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum gets to walk through the past.

It’s one of his favorite parts of the job, perusing hallways adorned with old cotton jerseys of the Homestead Grays and Kansas City Monarchs and Pittsburgh Crawfords; strolling by statues of Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson, Buck O’Neil and other stars of a bygone era; delivering well-practiced dissertations to one visitor at a time.

“This story is so much more than just a baseball story,” Kendrick said, his voice rising with emotion during a recent phone call from the museum in Kansas City, Mo. “This is a story of social injustice. It is a story of the civil rights movement. And it’s a story of overcoming all of that adversity stacked against them.”

He was hoping to amplify that message this summer, to celebrate the Negro Leagues’ 100th anniversary with several months of museum-organized events. The novel coronavirus pandemic derailed those plans. But the recent protests over social inequality have given him another type of megaphone instead His museum, he said, doesn’t just honor an often-overlooked history. It isn’t simply memorializing teams born out of segregation and the players who helped dismantle it. Now more than ever, he finds the Negro Leagues’ history reverberating today, connections to the present threaded within the story’s every stitch.

“The social justice upheaval we’re experiencing,” he said, “it magnifies and quantifies the value of our museum to a greater extent.”

Because every time Kendrick walks out of his office these days, he isn’t just walking through the past. He sees lessons applicable to the present, and ways to build a better future in baseball and beyond.

::

Negro Leagues historian Phil Dixon, 63, has published everything from books to photo albums to baseball cards over his decades of research, taking aim at misconceptions he feared distort the leagues’ legacy.

A common assumption, Dixon has found, is that the Negro Leagues were second-class, home to a few big stars that few fans ever got to see.

So, he and other historians have unearthed newspaper articles, photo archives, box scores — all manner of artifacts to paint an accurate picture of the leagues.

“I tried to break a lot of these long-held beliefs,” Dixon said. “Probably the greatest one was, ‘Too bad nobody ever saw these guys.’ That is a big lie.”

In reality, the Negro Leagues came to rival their MLB counterparts in attendance and in talent, Dixon said, overcoming the very discrimination from which they were created.

“It’s all built on one simple principle,” Kendrick explained. “You won’t let me play with you? Then I’ll create my own.”

No comments:

Post a Comment